- Home

- Thomas Brown

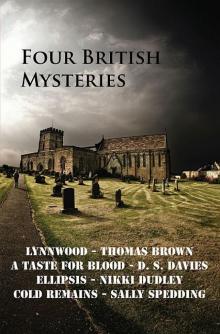

Four British Mysteries Page 3

Four British Mysteries Read online

Page 3

* * *

Harriet had been a vain woman, the product of modernity, but even she hadn’t been able to ignore the allure of the Forest, as though some part of her under that false face longed to be beneath the trees. It was a longing that had kept her from the Forest, in the same way that the hungry sometimes deny themselves food, for fear of overindulgence. Freya knew that now, although such a thing would never have occurred to her younger self, who only delighted that both her parents were walking with her. She drew comfort from that delight, from the old paths, the memories of simpler times.

She wrapped that comfort round her like a blanket. More than the cold or the arrival of winter she detected something else in the Forest; a gnawing uneasiness at the back of her mind. She didn’t see or hear anything untoward, but she couldn’t deny the weight she felt, pressing in from all around.

“What’s that?” George said suddenly. Lost in her thoughts, she had almost walked into him. He was standing in the middle of the path. She followed where he was pointing to a bird, a solitary magpie, perched on a sign.

“That’s a magpie, George.”

“No, not the magpie. I know what those are,” he said. “I meant the other thing.”

“What other thing?” She studied the Forest.

“There was a figure, by the trees. A person, I think, except it was hard to see properly because of the shade.”

“It was probably another person then,” she said. “You know, plenty of people from the village walk their dogs around here, like we do.”

“It reminded me of someone. My friend from the train tracks.”

“Your friend?”

He looked up at her with wide, impressionable eyes, the darkness of the Forest reflected in his pale face. “My friend. The man who lives in the tunnel.”

* * *

The memories are so clear now. She can hardly think, hardly breathe, for their clarity, after so long in the dark. That which was once clouded has run clear until she can think of nothing else. They sluice like the brook through her mind, its waters swollen with spring.

She pauses, pen in hand, and turns to the AGA cooker. The ache inside her redoubles, crippling in its intensity until she cannot move except to clutch her arms around her stomach. But these are not hunger pangs; they are aches of a different kind. It is not her stomach wrapped in her arms but her abdomen and the womb beneath, where her little ones first came into being, where they grew and from where they were born into this wilderness world. They are children of Lynnwood and now Lynnwood has them again. She feels hollow. Light-headed at the thought of what they have become. They are lost to her, devoured by the same hunger that threatens to consume their mother.

She moans helplessly, a low, bovine sound, before dropping her pen and clasping a hand to her mouth. Her eyes flicker to the window. Evening is fast fading. Shadows lengthen, spilling from the empty windows of Granary Cottage opposite, moving where all else is still. The building is tinged with the lingering pink of dusk. Soon there will be shadows of other things too; bony silhouettes peering into her house, crawling through the streets, slender arms reaching for her door. And she will answer them. She will open her house to Midwinter because there is no fighting it anymore...

There is not long left but there is still time, if she writes quickly. She retrieves the pen from the tabletop and places the nib to paper. With the smells of the Forest filling her nostrils and the haunting laughter of her children in her ears, she writes.

CHAPTER FOUR

The more that she ate, the more she surrendered to those instincts she had for so long been conditioned against, and the more she began to remember. It was a therapy of food; slim rashers of crisp pig, bursting sausages, eggs beaten to within an inch of their lives by her practised hands, as though not eggs but something else, transformed into dripping omelettes. It was only natural, she supposed, that these memories manifested in her dreams at first. What else are dreams, but memories of the past, the future; of what could have been, or might yet be?

* * *

She dreamt first of the Forest. She couldn’t see the brook from where she walked but she could hear it; a lively rushing of water through the trees. It was dark here, but not oppressively so; light broke through the dense canopy in wide pools, which scattered the shadows of the forest floor. Occasionally the path would take her through a glade or clearing, where more light reached, uninterrupted by leaves or branches. It must have been summer; delicate elf rings dotted the grass, inviting her to run through them, to jump from circle to circle, and dandelion seeds drifted languidly on the air.

Another figure moved behind her in the Forest. She could feel his presence; the press of his footfalls on the ground. She knew without looking that it was her father and that she was a little girl. The trees were taller, so much taller than she remembered them being, the grass much closer to her face. Wood pigeons warbled softly in the trees, as did a number of birds she couldn’t identify. She didn’t suppose it mattered; the birds sang and the forest air was pleasant. These were the important things. This, surely, was why the memory had endured, hidden for so many years. She felt dizzy with nostalgia.

Father and daughter moved deeper into the Forest. She saw other shapes now, twin shadows in the undergrowth: their two Cocker Spaniels, Ralph and Jack. The dogs moved through the shrubs without stopping, their noses never far from the ground. Occasionally they would collide, as the same scent brought them together. Playful yelps ensued, scattering through the trees, followed by laughter. She realised it was her own, and that she was smiling.

The brook drew closer. She could see the gap ahead, where the trees grew slightly apart, and she hurried towards it. She moved faster now. She seemed to be skipping.

Bauchan Brook, named after a local legend of Lynnwood, said that visitors to the water were watched by someone or something between the trees; a spirit of the wilds or perhaps the trees themselves, standing guard over the clear waters from which they drank. She had no such memories, no encounters that she could recall, but she couldn’t deny the presence that hovered over the place; a quiet watchfulness, seeming both young and old.

Except, this time when she stepped from the tree line, as she knelt to dip her hands into the water, she thought she did see something. A silhouette, crouched across the brook. She saw only its reflection first, broken and pale in the shining waters. Filled with curiosity she looked up, the figure across the brook doing likewise. Their eyes met and she felt a deep, irrepressible urge inside of herself, the likes of which she had never felt before. Then the brook seemed to expand, breaking its banks as the light washed down through the trees, and the trees themselves rose taller and thinner until there was nothing but that shining, liquid light and she woke, wet and hot, in bed.

* * *

Though Freya never actually saw her father in these dreams, he wasn’t far from her thoughts. David Heart was as shrewd a businessman as he was a devoted father, and he had always been there for his daughter.

“He was tall. And broad. I remember him being broad,” said Catherine, her eyes sparkling devilishly over a glass of white one afternoon. “Big, strong arms.”

“Catherine Lacey. You’re awful, do you know that?”

“Would you have me any other way?”

Despite growing up in the same school year as Freya, Catherine still seemed the more youthful of the pair. Her rotund face concealed age, and her portly figure, with her thick neck and generous arms, suggested a voluptuousness Freya’s slender shape lacked. Even so, the two remained as close friends as they had ever been. Where they had run through the heathland as little girls, now Freya’s dog gambolled over the grass. The poetry they had read at school filled Catherine’s bookcases. One collection comprised of Catherine’s own verse, though Freya had been forbidden from ever reading it. And the squash that they used to drink had become darker, stronger and much more alcoholic in nature, though they drank it with no less relish. Catherine had always possessed something of a nose for

“the good stuff”, ever since they first started sneaking bottles from her parents’ wine cellar after school. Raised on these fumes, it was only natural that the woman had grown up with a taste for them.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about him lately,” said Freya, staring over her glass into the garden. “About what happened to him, the unfairness of it. The disease took everything from him. That business was his life.”

“Everything! Remind me, did the business fail?”

“Well, no,” said Freya. “He sold his shares long before the end. There was no other way. He couldn’t run a company with dementia.”

“There we go,” said Catherine. “The wheels of industry kept turning. Some poor soul will have risen to replace him and that was the end of it, as far as they were concerned.”

“You’re saying his business lived on without him. Is this supposed to be comforting?”

“Yes! Consider that Sam Clovely. He took his seat on the village council so seriously, but what good did it actually do him?”

“He was mad, Catherine...”

“No, he went mad.” She rolled her eyes. “When you get down to it, it’s not work that matters, it’s not job titles or a place at the head of the business table. These things go on regardless. It’s Haven House. It’s your memories. It’s you.”

“Me?”

“You, your father’s seed, his flesh and blood –”

“You’re growing vulgar again,” said Freya, winking. “It’s too early in the evening for that yet.”

“Dress it up however you like.” Catherine took a large mouthful of her wine. “You know what I mean. There’s working and there’s living.”

Birdsong sounded from the garden. It was light, without worry. Freya watched as one of Catherine’s cats stalked a sparrow through the undergrowth. “I’ve been dreaming about him again,” she said.

“Your father?”

She nodded and Catherine smiled wickedly.

“I’ve been dreaming about him too. What would your mother have said?”

The cat sprang, the sparrow vanishing beneath its claws.

* * *

When not in Catherine’s company, Freya found herself increasingly drawn to Allerwood Church. She had lived a privileged life, all things considered. Her father worked hard to provide for his family and she had inherited generously on her parents’ passing. She visited the churchyard in the afternoons, once Eaton had been walked and the children were at school. The dreams gnawed at her resolve, their little teeth nipping at wounds long since healed until they were red and raw.

“It is clear you have something on your mind, my dear,” said Ms. Andrews, after they had exchanged pleasantries one afternoon. The vicar made her way through the graves, to stand by Freya’s side.

“Is it so obvious?”

“Indeed,” said Ms. Andrews. “I have a view of the church grounds from my windows. It’s really quite beautiful, in the summer. Pardon my saying, but you’re spending near as much time here as the dead. Is there anything I can help you with?”

“I don’t think so. Thank you, though.”

“You are sure, Freya? God is healing, you know, and failing that I have an excellent brandy in need of drinking.”

“I feel... I’m remembering things, that’s all.”

A curious look passed over Ms. Andrews’s face at these words. The woman seemed suddenly older and younger, almost childlike in her expression. She toyed with her hands behind her back.

“We’re all remembering things. Winter, it seems, has brought a host of memories this year.” She stared into middle-space for a moment, her wet eyes glistening. Then she smiled. “Come inside, let us talk and eat.”

CHAPTER FIVE

Shadows and a vacuous quiet filled the Vicarage with a rigid presence that seemed, momentarily, to still the waking hunger inside Freya.

With shaking hands, Ms. Andrews unscrewed a dusty bottle and poured two splashes of amber coloured liquid into glasses. The old woman sat across from her in the drawing room, which had the same stale air, Freya thought, as Allerwood Church. An effort had been made to soften the room and make it more hospitable, but not a great one. Varnished elm bookcases lined the walls, filled with volumes of texts, and a vase of lilies wilted on the windowsill. A plate of scones filled the table between the two women, small pots of jam and cream beside it. The smell of brandy blossomed in the room.

“Lynnwood is an old village,” said Ms. Andrews, sipping slowly from her glass. “The old ways still hold sway here, though there are few who see it.”

“Yes, we have a longstanding heritage here –”

“I see it, though,” she went on. “I notice these things. I know what to look for, especially of late. So I realise the importance of our church here in Lynnwood.”

“What do you mean?”

She indicated wildly to the bookcases, a drop of liquor spilling from her glass. Again, she did not seem to notice. “There are books, parchments and diaries here, which date back to the earliest days of the village. There are still more in the study. I have read many, although it would take another lifetime to read them all. These matters interest me.”

They sat in silence for some minutes. Freya expected Ms. Andrews to continue, to expand on her observations, but she seemed distracted, her eyes fixed over her drink. Freya had a short sip of her own brandy, which tasted as it had smelled, then prepared her scone out of politeness. They were freshly baked, she noted, probably bought at market that morning.

She was spreading jam when Ms. Andrews chose to speak again.

“We didn’t always have such comforts. Those early days were dark ones. I was unsurprised when I learned our church was among the first of the buildings to be fashioned here.”

“I had read similarly –”

“People always turned to God in those times. He was a means of coping, a source of spiritual strength, a means, they thought, of elevation from the beasts of the earth.”

Freya was surprised at the note of disdain in the vicar’s voice. “You think this has changed?”

“Of course it has, Freya. People don’t come to church anymore, not for God anyhow. I’m not sure if they ever really did come for Him. People’s reasons are generally their own.”

Freya felt herself blushing, but nodded and took another hurried sip of alcohol. It stung her tongue and cheeks.

“But enough of that,” said Ms. Andrews. “Tell me, what is it you remember?”

Warm and liberated by brandy and the frankness of her host, she recounted to Ms. Andrews honestly the dream that had filled her sleeping thoughts for over a week now. All the time that she spoke, the old woman watched her, nodding occasionally. Otherwise she was silent. Those loose, watery eyes stared right into her own, unafraid; an adult, listening to the anxieties of a child. Encouraged, Freya then spoke of her uneasiness, of the unrest she sensed in Lynnwood.

“It is strange that you dream of the Forest,” Ms. Andrews said finally, when she had heard everything.

“Is it?”

“Yes, you see, I too have been dreaming of it. Not memories, or pleasant, energetic dreams, as yours sound, but dreams all the same.”

The words that spilled from Ms. Andrews’s mouth that afternoon took firm, wild root in Freya’s head. She talked of horrible things, made all the more so for the righteous voice that spoke them. Freya couldn’t help but worry for the troubled mind that formed such fantasies, or worse, endured them, night on night.

* * *

Ms. Andrews’s dream was always the same; a woman with a housefly face and wings like stained church glass. Only each time she dreamt it was longer and longer before she woke from them. No matter how much she prayed when she rose each morning, or how softly she appeared to sleep, it was the same. And as her dreams deepened, playing out longer in her mind, she found herself approaching this figure in the Forest. She was helpless to move otherwise, no matter how much she struggled to turn, to run back through the trees, to the Vicarage

and home.

The figure under the trees was a horrible sight to behold. Ms. Andrews had thought she had seen her fair share of suffering in her life-time; her sermons preached often of lepers and she had worked with other, more unfortunate souls during the years of her service. But this woman, if she could even be called such, was by far the most abhorrent. Each night that Ms. Andrews dreamt, the figure took a step closer, and each night a little more of her became visible under the fading light.

Smooth, supple curves made up her human parts; pale, Elizabethan skin, soft and naked. Her legs were long but well-proportioned, her hips broad, as Sarah’s, blessed mother of Isaac. Then she saw the face of the woman, her large head that of a housefly, like the ones that crawled behind the curtains in the drawing room to die. Its flesh was mottled and leathery and its eyes were like fractured glass, or, she thought, morality, from the way that it looked at her; a thousand glittering facets, strangely human, staring from across the clearing.

And most unsettling to Ms. Andrews was that each step across the forest floor brought the uneasy apparition itself closer. Every step that she took was mirrored by the horrid, fly-shaped figure opposite; until she knew one evening they would meet.

It was always with this realisation, she said, that she woke, sweating, damp and with a thirst only alcohol would slake.

* * *

Every resident of Lynnwood knew its vicar, though few found need to call Joan Andrews by her first name. A polite, private woman to meet, this changed when she preached, as if in doing so she was forced to expend herself, to draw deep from within. The lessons of her life became the subject of her sermons. And they were righteous speeches. Her voice, deceptively strong for one so physically frail, carried far over the pews.

Freya had sat through more than enough of these sermons to piece together the old woman’s past, without their own private conversations taken into consideration. The rarer details of her history were imparted over cream tea and drink, such as they had taken the afternoon they discussed their dreams, and if she was an outspoken woman with a long life story to share, brandy only served to loosen her tongue.

Four British Mysteries

Four British Mysteries