- Home

- Thomas Brown

Four British Mysteries Page 16

Four British Mysteries Read online

Page 16

I grinned. ‘I’m anybody’s for a cuppa and a biscuit.’

* * *

Father Sanderson’s office was a cramped little chamber just beyond the vestry. It smelled of damp, dust and altar candles. Various tomes were piled up along the walls and there were a couple of bentwood chairs and a bench which also held books as well as a gas ring, kettle and other tea-making equipment. Alongside these were several goblets and a bottle of what I assumed was communion wine standing on an old newspaper. Around the base of the bottle, the paper was spotted with dried splashes of the wine, creating a delicate pattern in varying hues of red.

‘Sit yourself down, Johnny, and I’ll brew up.’

I did as he asked, wrapping my overcoat around me. For my money it was colder in here that it was outside in the graveyard. A few minutes later I was sipping a cup of scalding hot tea and nibbling on a damp digestive.

‘Sorry to bother you, but I’m in a bit of a quandary, really,’ said the old cleric as he seated himself opposite me. He had a kind, heavily wrinkled face framed by a thatch of thick white hair. I guessed that he was in his seventies, but he could have been younger: it was just that his desiccated skin and stooped shoulders suggested otherwise.

‘I know you are a kind of detective, Johnny, and I thought you might be able to offer me some advice,’ he began hesitantly. It was obvious that he felt awkward about having to approach me in this way.

‘If I can,’ I said. ‘What’s the problem?’

‘It’s one of my parishioners, Annie Salter. She’s a widow. A lady in her fifties. Lost a son at Dunkirk. Been a regular at St Saviour’s for many a year. A few weeks ago I found her in the church. She was praying in one of the pews near the altar and seemed upset. She was muttering something. I could not hear the words but it was quite clear that she was asking for help – for divine assistance. I stood in the shadows not wanting to interrupt her private moment. From time to time she would pause in order to stifle a sob and then she would begin again. My heart went out to the poor soul. Whatever afflicted her, it was tearing her apart.

‘I waited at the back of the church while she had finished and then as she made to leave I approached her. I could see clearly that she’d been crying – and I thought I might be able to help her. Offer comfort, at least.’

‘What is troubling you, my dear?’ I asked, taking her hands in mine.

She tried to shrug off her distress with a faint smile. ‘I’m all right, really. Just feeling a little low. Came in to ask Jesus for some help. It’s the war, isn’t it? Sometimes it gets you down a bit.’

I knew that she was not telling me the truth. Not the full story, at least. I told her that I was there to listen, to help. I was one of Jesus’s helpers. Perhaps I could come to her aid. My offer of help seemed to upset her more than ever.

‘At the moment, I don’t think anyone can help me,’ she told me as her eyes moistened again. Then she pulled her hands from mine and hurried away without further words or a backward glance.

‘That was the last time I saw her.’

I said nothing. I knew that there was more to come. There had to be.

‘The following Sunday, Annie did not turn up for the Sunday service. I had not known her to miss in three years, apart from one occasion when she was struck down with influenza. The following morning, I went round to her house to see if she was ill and needed some help. There was no reply when I knocked on the door. I knocked hard, I can tell you, Johnny.’ He smiled. ‘A priest always does. Sometimes the householder will hide behind the door hoping I’ll go away. If you bang loud enough, eventually guilt makes them open up.’ His smile broadened and then faded quickly. ‘But on this occasion there was no reply. I was just about to leave when the lady next door popped her head over her threshold. ‘I’ve not seen her since Friday. I reckon she might have gone away,’ she said. ‘Where to?’ I asked and received a puzzled shrug in response.

‘Annie’s behaviour in church and her absence prayed on my mind. I was worried about her – so much so that I visited the house again the following Thursday. Still there was no reply. My concern grew. I thought it was time to take further action so I went down to the local bobby shop on Frampton Street. They know me down there and took my concerns seriously. Sergeant Harmsworth came back to the house with me and after the rigmarole of knocking and waiting, waiting but no response, he applied his weight to the door and forced it open. ‘It’ll be up to you, Father, to pay for any repairs,’ he said trying to lighten the mood of the operation. We stood on the threshold and he called out Annie’s name. His voice echoed through the innards of the house but no one answered. I feared the worst. And so did Sergeant Harmsworth if his grim features were anything to go by. We moved into the tiny hallway and then into the kitchen. All was neat and tidy. All perfectly normal, I suppose. And then we came into the living room. It was terrible, Johnny. Simply terrible. There she was dangling from one of the beams, her mouth agape, tongue sticking out, her eyes… her eyes… well, it was terrible.’

‘She’d hung herself.’

Father Sanderson shot me a glance. ‘Well, that’s what it looked like. There was a dressing gown cord tied around her neck and a stool on its side under her. And there was a note on the mantelpiece.’

‘What did it say?’

‘I can tell you exactly what it said. Just five words only. ‘I just couldn’t go on.’

‘A fairly traditional sentiment for a suicide.’

‘Mmm. Exactly. Traditional. Cliché even. Oh, the police are quite convinced that poor Annie committed suicide.’ He paused and flashed me a piercing glance.

‘But you’re not,’ I said.

‘No, I’m not. It’s not her way. She was far more stoical than that. She’s not a quitter. And another thing… that note. It’s not her writing.’

‘You told the police this.’

‘Of course I did. They just said that when a person is in a disturbed phase of mind their handwriting goes haywire. They can’t control their movements or some such notion. But I know, Johnny, I know that Annie did not write that note. Apart from the writing, it was too brief and trite for Annie.’

‘What are you saying?’ I asked, fairly certain I knew the answer anyway.

Father Sanderson looked me in the eye and said sternly, ‘I am saying that she was murdered.’

THREE

Dr Francis Sexton sat in his car and stared through the windscreen at the forbidding building before him. Even on a bright day in March when the sky was making every effort to shrug off the greyness of winter and allow little patches of blue to appear, Newfield House looked bleak and gloomy. To Sexton the building, stark against the bright sky with drab stonework marked with the strands of long-dead ivy, and the strange acute angles of the gables, along with the blank shuttered windows, made the place look like an illustration from a work by Edgar Allan Poe – The Fall of the House of Usher – maybe. The house, an early Victorian monstrosity, stood in isolation in its own grounds, now uncared for and neglected, like the inmates within.

Sexton shifted his gaze to the paint-peeling notice erected near the main door:

Newfield House

Psychiatric Hospital

No Unauthorised Admittance

Home Office Property

Newfield House, once the house of some rich industrialist, had been converted to a lunatic asylum for the criminally insane as an overflow of Broadmoor and had only been renamed within the last ten years. The name may have changed but the purpose and régime remained more or less as it always had. There was little psychiatry practised there. It was just a matter of keeping the inmates contained and sedated. The state had seen fit not to hang them, so instead they must rot in a drug-induced state in this God forsaken place near the Essex marshes. Sexton could understand and to some extent sympathise with these sentiments. The twenty inmates had all committed horrendous crimes while ‘the balance of their mind was affected.’ Madmen, then. But as Sexton knew, madmen could also be rational

and reasonable for most of the time. It should be possible to rehabilitate these creatures so they could return to society. They did not ask to be mad – just as a man who is deaf or blind or a fellow with a lisp did not ask for these disabilities. Madness was a disability. It was Fate or God who allowed it. It was up to man to help, not to condemn. That, at least, was the litany that Dr Francis Sexton preached and that is why the authorities with great reluctance allowed him to attend one of the inmates at Newfield for ‘research purposes’. Sexton was writing a book on the human psyche with particular attention to the diseased criminal brain. That is what the authorities believed and that is why they permitted Dr Francis Sexton to visit Newfield the third Thursday in every month to spend time with one of its notorious inmates: Ralph Northcote.

* * *

The said inmate Dr Ralph Northcote waited for his visitor in a small, featureless room that had become his home for the last eight years. His cell, in fact. It consisted of a bed – clamped to the floor so that it could not be moved – a chair, a washbasin, and a small bookshelf crammed with medical volumes he had managed to retain from his old life and a barred window which was too high for him to peer out of, even if he stood on the chair, which he had no inclination to do. Northcote was no longer the lithe, clean-shaven charmer of his younger days. Not being able to shave unless under strict supervision, he had grown a straggly beard while boredom had led him to consume as much of the foul institutionalised food as he could. He was now a rotund, heavily bearded, blotchy-faced parody of his former self, looking much older than his forty-eight years. He certainly no longer resembled the man who had stood in the dock accused of a series of horrendous crimes. The man the press named as ‘The Ghoul’.

Northcote was particularly excited about today’s visit from his new friend, Francis. His monthly visits had become the highlight of his life in this dreary place. They thought him mad and that’s why they had dumped him in this hellhole, to be forgotten, to rot until death. He wished they had hanged him. That, at least, would have been the end of it. He was not mad. He had known what he was doing. He would do it again – given half the chance. His passion for raw flesh may seem strange to the outside world, but to him it was no different from stuffing your face with bits of dead cow, pig or chicken. He was convinced that it was because of this fact that the judge hadn’t dared to pass the death sentence. The old fool knew he was not mad but couldn’t condemn him for his unusual appetite.

At first he had resented Francis Sexton’s visits. He only agreed to them because they would bring some kind of novelty to his drab routine. But he didn’t want to be scrutinised, analysed, compartmentalised and patronised. However, he soon realised that Francis would do none of these things. He had come in a spirit of friendship. Of course, he asked questions – wanted to know things about him, his history, his thoughts, what made him tick. But friends did that. And they had become friends. He knew that Francis grew to value these visits as much as he did. Northcote believed that a bond had grown between them and that was because Francis really understood him and his predilection.

Francis was the only one who had really listened to him, listened and understood his passion. He felt at ease with this man and was able to tell him things he had never confided to anyone else. Things about his childhood and his first encounter with uncooked flesh and the revelations that this had brought about. Francis never condemned or criticised him. Indeed, he began to smuggle in little treats: a piece of liver, a small cut of beef, and some pork. All uncooked and red with blood. It was their little secret. A secret that bonded them even closer.

And then the plan had developed. An idle remark. A casual aside. But it had created a spark with gradually ignited and the plan flickered into life.

And today was the day to put it into operation.

Through an innate ability to master his emotions, and a learned facility developed from being shut away in this Godforsaken dump, Northcote was able to maintain a cool and collected outlook even when exciting and dangerous things were about to happen. As he sat in his cell patiently waiting for the arrival of his visitor, the observer would have noticed nothing about his appearance to suggest a mood of suppressed anticipation and excitement. Except perhaps for the gentle – ever so gentle – movement of Northcote’s thumbs. While all other parts of his body remain statue-like still, his thumbs circled each outer in a lazy moribund fashion. It was the one chink in his armour, his one expression of inner excitement. Meanwhile the eyes were dead, glacial and dead, and the body remained rigid with the feet splayed flat on the floor. You could hardly tell the man was breathing.

But the thumbs continued to move like comatose butterflies.

* * *

As was his usual practice, Dr Francis Sexton kept on his hat, scarf and coat once he was inside the building. He was such a regular visitor to Newfield that he only had to flash his authorisation in a casual fashion to the guard on reception before he was allowed to pass through the locked section into the hospital.

‘You here again?’ asked the guard in a cheery fashion, hardly looking up from his library book, a western with the title ‘Me, Outlaw’.

Sexton nodded.

‘Hardly seems five minutes since the last visit.’ The man chuckled. ‘Time flies when you’re having fun.’ He chuckled again at his own sarcasm and returned to the dust of Arizona.

Sexton made his way to E block where Northcote’s cell was situated. It was a cold, gloomy building with the smell of damp and decay always in the air. The décor was a mixture of the faded and neglected original Victorian furnishings and the utilitarian touches institutionalised grimness. He passed a few staff on his way but no one took much notice of him or gave him a greeting.

Eventually he reached E block and passed through swing doors which led him down a short tiled corridor at the end of which was Northcote’s cell: E 2. A young man in a white coat sat outside the room. It looked to Sexton as though he had dropped off to sleep – and who could blame him, sitting on guard outside a madman’s room just in case he became unruly, agitated, violent. To Sexton’s knowledge, Northcote had exhibited none of these symptoms since he had been admitted eight years ago. The sound of Sexton’s shoes clipping sharply on the tiled floor seemed to rouse the young man from his doze. He glanced up and observed the approaching visitor. Before the doctor was upon him, he recognised that grey overcoat and the black fedora. He rose to his feet and taking a key from the pocket of his white coat he slipped it into the door.

‘A glutton for punishment, I reckon that’s what you are,’ grinned the young man sleepily.

Sexton emitted a non-committal grunt.

The door swung open and he entered the cell. No sooner had he done so than the door clanged to behind him.

Northcote rose from his chair and the two men stood facing each other, neither of them opening their mouths, but their eyes spoke volumes. Gradually Northcote raised his right arm, and extended it towards his visitor. Sexton took it and the two men shook hands.

‘Dr Sexton, it is so good to see you,’ said Northcote in his strange gravelly voice, which had developed since his incarceration. He spoke little, hardly a few sentences a day, and it was as though his vocal chords had become rusty and were in danger of seizing up.

‘And you too, Ralph,’ he said with a ghost of a smile, as he placed his briefcase on the floor.

Northcote’s eyes darted in its direction, wide with anticipation. ‘You have perhaps brought me some treats.’

‘Later. For now, it is time to get rid of that beard.’

Opening the briefcase he extracted a small cardboard box and handed it to Northcote. It contained a pair of scissors, a shaving brush and a piece of shaving soap. ‘Put the débris in the box,’ said Sexton.

Moving to the little sink with a piece of aluminium which acted as a mirror, he began chopping away at his unruly growth. Sexton, took off his hat, coat and scarf and sat on the bed to watch. Ten minutes later, Northcote had completed his task. Scratching h

is chin, he turned to his visitor. ‘Well, what do you think?’

‘Well, you look like the ghost of Christmas Past, but at least you don’t look like you did.’

‘Feels strange,’ Northcote said, rubbing his chin. ‘But that’s good. Anything which has a touch of novelty is good in this place. Now, can I have my little treats?’

Sexton nodded and retrieved a small damp brown bag from his briefcase. ‘A little liver,’ he said. ‘Fresh meat is very hard to come by at this time,’

‘The war, you mean?’

‘Yes, the war.’

Northcote shook his head. ‘I know nothing of the war in this shabby cocoon.’ He tore open the bag and his eyes flickered with glee at the sight of the slimy red offal. There were two pieces each about the size of a child’s hand. He snatched one up and slapped it to his mouth and chewing on it noisily for a few seconds, sucking the blood from it, before he bit into it. He gave a gurgle of delight as he chomped on a ragged fragment. Sexton watched with fascination as with the serious deliberation of an animal Northcote devoured the liver, slowly but with enthusiastic relish. When he had finished his lips and cheeks were smeared red. He looked like a crazy clown.

’You’d better clean your face,’ said Sexton with a half smile.

‘A little water clears us of this deed,’ replied Northcote moving to the sink where he ran the tap and swilled the blood away. He stared as blood, now pink diluted by the water, spiralled away down the plughole.

‘Thank you,’ he said. ‘That was most tasty. I get nothing like that in here. Everything is incinerated before it reaches a plate.’

Sexton ignored the remark. He had heard many similar ones before. It was Northcote’s usual and predictable mantra after consuming his meaty titbit.

‘Are you ready? Are you prepared?’

Northcote nodded. ‘I am.’

* * *

The young man was interrupted from his day dream – a languorous affair that featured one of his favourite film stars in a state of undress – by a tapping on the door of cell E 2.

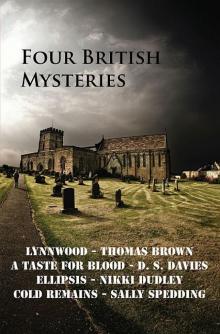

Four British Mysteries

Four British Mysteries